“Do you ever speak on utility crisis communications?” Barry Moline, executive director of the California Municipal Utilities Association, asked me in a recent phone call. I told him I did. He asked if I could speak on that topic at CMUA’s annual conference. I told Barry I would be delighted. Readers interested in my take on utility crisis communications can check my previous blog posts, like here and here and here.

True or False: Most Crises Take Place Outside an Organization

Maybe true. Maybe false. What we do know is that crises take place inside and outside organizations. What also is clear is that it’s generally easier for communications professionals to discuss a utility’s crisis communication response to an external event like a flood or tornado. Communications tied to internal problems tend to be more difficult.

Other speakers on that CMUA panel were scheduled to discuss their crisis communications work on external events: last year’s California wildfires and the potential collapse of a spillway at the Oroville Dam, the state’s second-largest reservoir.

Where could I add value to that panel? What wasn’t being discussed? I thought about the role organizational culture played in internally generated crises that have engulfed businesses and people in recent years: sexual misconduct in the workplace; United Airlines dragging a passenger off one of its planes; performance-enhancing drugs in sports; the malfeasance of financial firms that created the housing bubble and the Great Recession; and Enron.

That was just off the top of my head. All those crises were enabled, or nurtured, by the organization’s culture.

Rather than discuss best practices in utility crisis communications, I thought it would be more useful to discuss how utilities could prevent internal organizational crises at the outset, and thus lessen the need for utility crisis communications down the road.

Utilities can’t control severe weather events like tornadoes, hurricanes, flooding or blizzards. There’s little they can do to prevent a wildfire caused by an untended campfire or an idiot tossing a lit cigarette into a tinder-dry forest. All of that takes place outside a utility.

So I decided to talk about what utilities can control: What employee behavior is encouraged, tolerated or forbidden in their workplaces? In other words, the role a utility’s organizational culture plays in preventing, or permitting, a crisis.

If an ounce of prevention really is worth a pound of cure, as our parents told us, why not urge utilities to prevent scandals and crises that spring from their organizational culture?

Preventing internal, organizationally driven scandals and crises could save utilities from having to spend millions of dollars on crisis communications experts and litigation. It also could avoid the potentially significant reputational damage when a toxic workplace erupts in flames in full view of the public and investors.

Communications tip of the month: Organizational culture is a powerful tool. Utility employees at all levels can prevent future culture-driven crises if they work proactively and communicate clearly about what behavior is encouraged, what is tolerated and what is prohibited.

True or False: Organizational Culture Has Nothing to Do With Preventing Communications Crises

False.

Think about it: The organizational or “bro” culture in Hollywood, Silicon Valley and Wall Street, among other places, provided the necessary precondition for the mistreatment of women that eventually gave rise to the current #MeToo movement. That bad behavior was, at some level, tolerated if not encouraged by higher-ups, typically because the misbehaver generated a lot of money for the organization. Harvey Weinstein (left) wasn’t the first Hollywood mogul to mistreat women, but his case is a useful illustration of how far an organization would go to tolerate aberrant behavior from a moneymaker.

Organizational culture does not exist in a vacuum. It is a living, evolving force that permeates every aspect of an organization. No one person controls it. In fact, it is the collective expression of everyone who works in an organization, as I mentioned in last month’s EEC Subscriber Exclusive.

True or False: The “New York Times Page One-Rule” Can Reduce the Need for Crisis Communications

True.

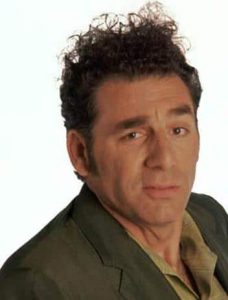

I first learned of the “New York Times Page-One Rule” when I was managing media relations for a utility some years ago, back when newspapers were still profitable, reporters were still trusted and social media was a far-off blip on the horizon. In today’s digital world, social media has become the new version of the “New York Times Page-One Rule.” Just ask Michael Richards (right), formerly of “Seinfeld” fame, whose career went from top-tier to toxic after a racist rant in a comedy club was captured in a cell-phone video. The rest, like Richards’ career, was history.

Social media deprived Michael Richards, Matt Lauer, Roy Moore. Kevin Spacey and other powerful people of a private space where they could commit dumb or unsavory or despicable or even illegal acts. Now, thanks to social media, we don’t have to wait until the next morning when the New York Times is delivered to our doors or our email inboxes. We can be alerted to boorish, vile or illegal behavior pretty much as it happens by opening Twitter or Facebook.

If you don’t want to be embarrassed, ridiculed, shamed or shunned, then don’t make unwanted advances on your coworkers, don’t file that false travel report, don’t drink and drive, and don’t give a no-show job to your brother-in-law. In other words, be above suspicion.

And because a lot of sketchy behavior involves at least one other person — either as a victim or a collaborator or a facilitator — today’s social media-driven infosphere means keeping bad behavior under wraps for long is pretty much impossible.

True or False: We Can Wait Until this Blows Over

False. Don’t try to “Slow Walk” the truth if a crisis erupts.

If a utility employee is caught doing bad deeds, the utility must own up to it immediately and make amends, I told the CMUA audience. Don’t slow-walk the truth. Pick one story (I recommend the one marked “truth”) and stick with it. Commit to fixing the problem. Then fix the problem.

Though it happened after my talk, Starbucks did all the right things in responding to an incident of racial profiling in one of its coffee shops in Philadelphia. I imagine that company’s response to a crisis will become a staple of crisis communications courses and workshops, alongside Johnson & Johnson’s response to the Tylenol contamination in 1982.

Utilities that encountered crises in recent years, including Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, Memphis Gas, Light & Water, Cobb EMC and Pederrnales Electric Cooperative, among others, created additional problems when they were slow or parsimonious with the truth following the initial allegations.

Because the Major League Baseball season was about to begin when I spoke at the CMUA conference, I shared a stark example of how to respond to a crisis, and how not to.

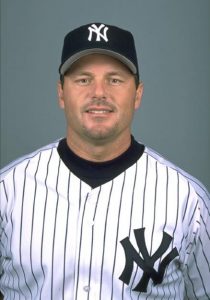

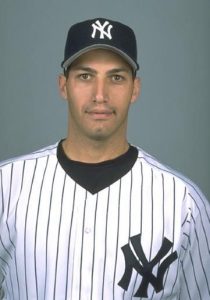

As longtime readers know, my favorite baseball team is the New York Yankees. Performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) cast a shadow over two Yankees pitchers some years back: Roger Clemens (below left) and Andy Pettite (below right). To make two long stories really short, Clemens was caught using steroids, but denied it repeatedly. Pettite admitted he used a prohibited substance once, said he’d never do it again, apologized to fans and to Major League Baseball and, to all accounts, has lived a scandal-free life thereafter.

I don’t know if either Clemens or Pettite will get into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Clemens won many more games than Pettite (partly because he played longer). But Clemens will always have an asterisk alongside his name in the minds of many sportswriters, players and fans. He won all those games during baseball’s PED era. Pettite played in that same era, but I don’t believe he carries that same stigma.

What’s all this mean for utilities? Following the Golden Rule (treating others as you would want to be treated) prevents organizational crises, keeps you in compliance with the “NYT Page-One Rule” and averts negative mentions in social media. All of that will help boost employee morale, increase customer satisfaction and create a safety net of stakeholder goodwill that can shorten the recovery time from future problems and crises.

Many communications crises can be prevented with careful planning and purposeful action.

Many communications crises can be prevented with careful planning and purposeful action.