When the Financial Times, one of the world’s oldest and most authoritative business dailies, and the “Dilbert” cartoon strip independently explore the same issue at about the same time, that’s worthy of note. And the issue is one near and dear to my heart, and hopefully yours: the need to communicate using clear English.

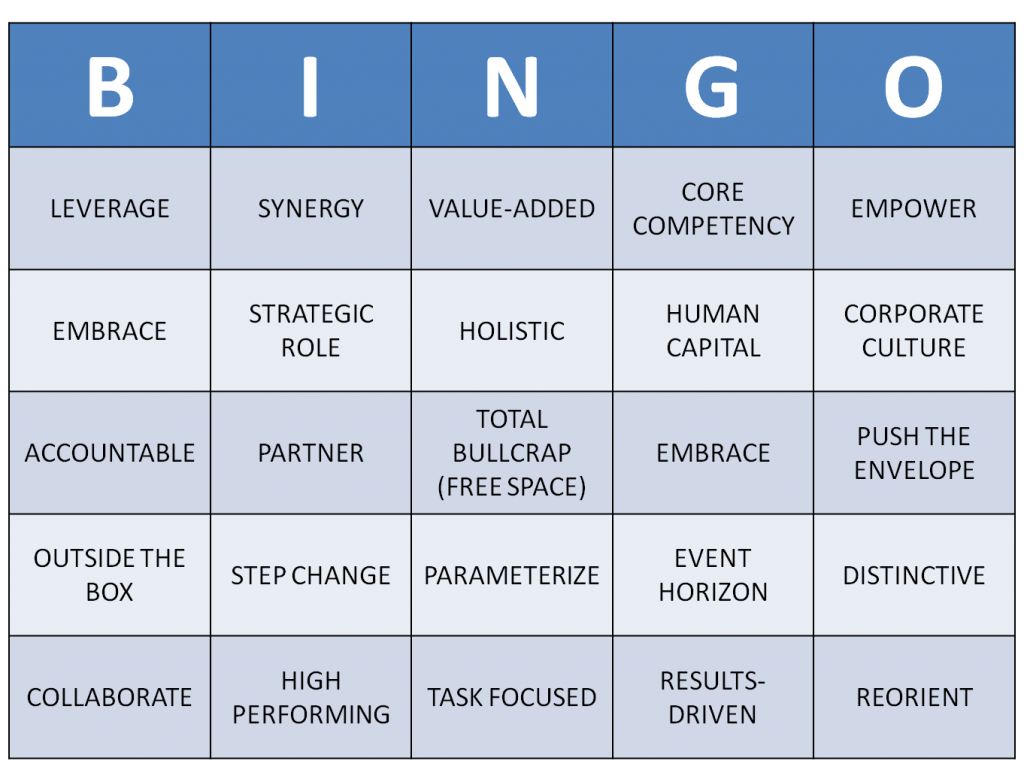

Have you ever played buzzword bingo? It sometimes helps soothe the pain of corporate meetings. I have played it, and it’s a lot of fun, particularly during those day-long planning retreats where senior management and consultants take turns exchanging the latest business buzzwords.

Playing buzzword bingo (a sample card is below; or visit a buzzword bingo generator site to create your own) is an employee’s quiet pleasure for being compelled to listen to corporate drivel. To play buzzword bingo effectively, you’ll need to listen carefully to the fusillade of words being squeezed out by the speaker, to ensure you don’t miss an opportunity to check off a box. If your leadership team notices your keen focus, so much the better (unless they find the card, of course).

Each year the Financial Times recognizes the worst examples of corporate obfuscation and double-talk with its Golden Flannel Awards. The results, posted in January, were revealing: How many of these screamers have you heard in your office?

- “Sweat the footprint”

- “Wet-bench testing”

- “Merchant stickiness”

- “Executive brownout”

- “Be cognizant of the optics of your personal brand”

- “Ventilate underperformers”

- “Master experts” and

- “Reinvest in our most impactful priorities”

The FT has become very parsimonious about making free content available to non-subscribers, so if the link to the article doesn’t work, you can listen to the author reading her column in a podcast.

Communications Tip of the Month: Communicating—either in written form or orally—is a craft that blends art and science. Using words like “synergy,” “leverage” and “step change” in your communications is a quick and sure way to undermine your communications effectiveness. “Smart talk” isn’t smart when it’s a substitute for actual thought and precise expression.

Compare the FT’s findings with this recent Dilbert cartoon strip:

Again, raise your hand if any of that sounded familiar.

The Dilbert strip and the FT Golden Flannel winners are calling out a corrosive trend of using words to obscure, rather than clarify. It’s called “smart talk,” and it’s not new. Harvard Business Review published an article on it years ago, about the first time we started hearing words like “bandwidth” and “mindshare” in the office. “The elements of smart talk include sounding confident, articulate, and eloquent; having interesting information and ideas; and possessing a good vocabulary,” wrote Jeffrey Pfeffer and Robert I. Sutton, the authors of that HBR article.

Their criticism of smart talk is that it can often become a substitute for action. Here I’m simply noting how smart talk amounts to an attack on clear thinking and effective communicating.

Ever been on a cross-functional team charged with crafting a new mission statement? Then you’ve probably heard more than your fair share of smart talk. Or, if you’ve ever listened to management consultants deliver their recommendations, you were probably swimming in smart talk.

The FT uses the term “guff” as a synonym for obfuscation, euphemism and rhetorical ugliness. Here in America, we might use an equally short and ever-so-earthy word to describe the same thing.

You can ward off some of the guff in the business world by poking fun at it, but all that guff has a pernicious long-term effect: By dulling our brain and narrowing our vocabulary, it makes us less able to think, and communicate, clearly and persuasively.

As communicators and marketers, each of us has the ability to resist our society’s mindless march toward mediocre thinking and communicating. In his classic essay, “Politics and the English Language,” George Orwell gives us six rules to guide our efforts:

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

If you want to see how readable your copy is, enable the readability tool in Microsoft Word’s “Spelling & Grammar” function. Among other things, that tool will tell you what percentage of your sentences are passive and the typical level of education required to understand your prose. In both cases, the lower score is better, like golf. To improve your score, use smaller words and write shorter sentences.

Communicating—either in written form or orally—is a craft that blends art and science. And like other crafts, such as carpentry and throwing curveballs, the skill improves with practice. So bring your “A” Game, step up to the plate and don’t short-arm it. Repurpose your skill set. Bite-size your copy. Leverage your human capital. Become best-in-breed. And don’t be afraid to disintermediate.

——————————————————————————————–

How Well Was Your Utility Prepared for The Promised Land?

Matt Damon and Gus Van Sant have a track record. The A-list actor and award- winning director first teamed up in Good Will Hunting. When Damon and Van Sant announced their second film collaboration, Promised Land, energy companies had good reason to be concerned. The film touched a hot-button topic in the energy field: production of oil and natural gas using a technique called hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking.” And, if Promised Land made a big splash, would that also soak the electric and gas utilities who have grown dependent on fracked gas?

Matt Damon and Gus Van Sant have a track record. The A-list actor and award- winning director first teamed up in Good Will Hunting. When Damon and Van Sant announced their second film collaboration, Promised Land, energy companies had good reason to be concerned. The film touched a hot-button topic in the energy field: production of oil and natural gas using a technique called hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking.” And, if Promised Land made a big splash, would that also soak the electric and gas utilities who have grown dependent on fracked gas?