Aaron Sorkin is an acquired taste. I get that. But whether you like your Hollywood honchos to be red-meat Republicans, like Clint Eastwood, or dyed in the (blue) wool Democrats like Sorkin, you can’t help but admire Sorkin’s rare talent. “A Few Good Men,” starring Jack Nicholson, Tom Cruise and Demi Moore, was his first paying gig as a screenwriter. He followed that by writing “The American President,” a movie starring Michael Douglas, and “The West Wing,” a TV drama starring Martin Sheen.

More recently, he was the wordsmith behind the movies “The Social Network,” “Moneyball” and “Steve Jobs.” Sorkin has his quirks, and he doesn’t always hit home runs, but when he swings for the fences — and connects — the ball can leave the park in a hurry.

I’m riffing on Sorkin because I recently binge-watched “The Newsroom,” a TV drama that was one of his towering, no-doubt moonshots. Throughout the series’ three-year run, there was a lot of food for thought for those in the media or communications business. Jane Fonda played the chief executive of a media company which owned a cable TV network around which the series was built. Her character had a particularly telling bit of crisis-communications wisdom in the series’ final episode. After listening to another TV executive complain about how his image is taking a beating in the press, she retorted, “You’ve got a PR problem because you have a real problem.” In other words, before you blame the media for your PR problem, consider the possibility that you have an actual problem.

In some ways it’s sad that we need a writer as talented as Aaron Sorkin to remind us there is a difference between reality and perception, substance and spin. In today’s optics-obsessed culture, when images can be manipulated and facts often seem negotiable, it was worth being reminded — albeit in a fictional TV drama — that PR problems more often than not stem from real problems. Bad acts create PR problems.

In recent weeks, we’ve seen some PR black eyes handed out for eminently good factual reasons:

-

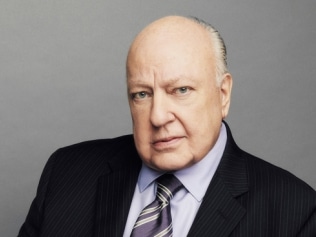

Credit: Adweek Roger Ailes, longtime head of “Fox News,” was forced out when his lengthy alleged history of sexual harassment of female employees came to light after one of them, Gretchen Carlson, sued him. Subsequently, numerous female staffers said they, too, had been the victim of Ailes’ unwanted attention.

- Melania Trump’s speechwriter plagiarized Michelle Obama’s 2008 speech introducing her husband to the Democratic National Convention.

- Debbie Wasserman Schultz was forced out as head of the Democratic National Committee after WikiLeaks posted DNC emails showing she was a Hillary Clinton partisan, not an impartial leader of a national political party.

- Volkswagen was forced to pay about $15 billion to settle claims in the U.S. after it admitted installing technology on 11 million of its cars that allowed them to fraudulently pass EPA emissions tests.

Supporters of Ailes, Donald Trump, Wasserman Schultz and Volkswagen reflexively dismissed their respective problems as small beer, utterly without substance and driven entirely by detractors. But the facts quickly came to light. These were real problems that became PR problems.

Case in Point #1: Middleborough Gas & Electric

As those PR problems unfurled, I had a chance to catch up with one of my favorite colleagues, Sandy Richter, communications manager for Middleborough Gas & Electric, a locally owned gas and electric utility south of Boston. She was telling me about a talk she gave a few years back on how she handled a crisis that erupted at her utility.

Sandy’s PowerPoint deck is absolutely indispensable for utility communicators eager to get some perspective on PR crises.

Middleborough G&E’s PR crisis started with an internal spat between the general manager and the treasurer over investment practices. This internal tiff was compounded by the GM’s refusal to listen to the concerns of town leaders about these investment practices.

Then came the inevitable citizen’s request to see a copy of the GM’s employment contract, which was public information but which the GM refused to provide. Turns out he had reason to be defensive: At over $160,000 per year, it was beyond generous — it was the highest for any public power general manager in the state. And his perks were lavish as well. He probably knew all this, which is probably why he fought so hard against releasing the information.

It was Watergate that popularized the notion that the cover up was worse than the crime. That was certainly the case in Middleborough. And it was certainly the case for other scandals in the utility business, including locally owned utilities Pederanales Electric Cooperative in Texas and Cobb EMC in Georgia. In both of those cases, what executives initially dismissed as just “bad PR” were eventually shown to stem from bad acts committed by company executives.

It appears Pacific Gas & Electric is going through the same “bad facts lead to bad PR” cycle now, as facts emerging in a trial over the San Bruno pipeline explosion appear to show the utility scrimped on safety in order to keep its earnings up.

Communications Tip of the Month: Bad PR usually stems from bad acts. Use EEC’s checklist, “Is Your Utility Headed for a Communications Crisis?” to take an honest and ruthless internal inventory of the things that could lead to public embarrassment, and then start fixing the problem.

PR Problems Can be Easy to Avoid

There would be fewer crises about which to communicate if those with power followed what has been called the New York Times “Page-One Rule”: If you don’t want to see unflattering stories about you or your company on the front page of the newspaper, don’t engage in sketchy behavior.

Specifically:

- Pay your employees fairly.

- Treat your employees as you would want to be treated.

- Make sure your workplace is as safe as it can be.

- Don’t steal from the company.

- Don’t award no-show contracts to your brother-in-law.

- Don’t dump poison in a nearby river.

- Don’t sell unsafe products.

- Don’t have extramarital affairs.

- Don’t cheat.

But because not every company follows the New York Times Page-One Rule, crisis communicators will not be going the way of buggy-whip manufacturers any time soon. Indeed, in today’s optics-obsessed world, where citizen journalists work alongside real ones, crisis communications is a growth industry.

Case in Point #2: MLGW

One utility that learned some hard lessons about crisis communications, and then set out to make sure it would never have to learn the same lessons again, was Memphis Light, Gas & Water (MLGW), a multi-service, locally owned utility in Memphis, Tennessee.

One utility that learned some hard lessons about crisis communications, and then set out to make sure it would never have to learn the same lessons again, was Memphis Light, Gas & Water (MLGW), a multi-service, locally owned utility in Memphis, Tennessee.

Before I launched EEC, I was a research director at E source and I was able to speak at length with Glen Thomas, at the time MLGW’s supervisor of media relations, about the lessons learned from its near-death PR experience, which involved a raid of its headquarters by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other law-enforcement agencies.

Glen’s takeaways included things like a utility having a humble public persona, admitting when it’s wrong and then showing the public what it’s doing to fix the problem. All true, to be sure, but then he recommended utility communicators hone their crisis communications skills with a weekly exercise using a different real-world scenario. Real-world practice, Glen recommended, is the only way to keep your skills sharp. At the time, MGLW used The Media Trainers, a crisis communications firm run by Eric Seidel that I can recommend.

Walking the Walk

In previous blogs I have written that most utility PR crises originate in a company’s culture particularly when there is an institutional disconnect between what the company says and what it does. In other words, talking the talk but not walking the walk. Earlier this year I blogged about an interesting company, Novareté, which helps companies clarify and communicate its values to employees.

In previous blogs I have written that most utility PR crises originate in a company’s culture particularly when there is an institutional disconnect between what the company says and what it does. In other words, talking the talk but not walking the walk. Earlier this year I blogged about an interesting company, Novareté, which helps companies clarify and communicate its values to employees.

To help utility communicators prevent their next PR crisis, I prepared a qualitative checklist so they could perform a self-assessment of their organization and its relations with its stakeholders, including customers and employees. A crisis can originate either internally or externally, but with social media and the 24-hour news cycle, you can bet the whiff of scandal will rapidly spread. How far and how quickly it spreads depends on the specifics of the bad behavior. I invite you to check out this free resource, and start working today to prevent tomorrow’s PR crisis.

To help utility communicators prevent their next PR crisis, I prepared a qualitative checklist so they could perform a self-assessment of their organization and its relations with its stakeholders, including customers and employees. A crisis can originate either internally or externally, but with social media and the 24-hour news cycle, you can bet the whiff of scandal will rapidly spread. How far and how quickly it spreads depends on the specifics of the bad behavior. I invite you to check out this free resource, and start working today to prevent tomorrow’s PR crisis.