“Thought leadership” is a term you hear a lot these days. I’ve penned a few “thought leadership” pieces over the years. But today, I thought I’d go back and ask, only slightly tongue in cheek, what recommendations Plato (left) and Aristotle might make if they were your energy communications consultant.

I think you’ll find their words of wisdom, spoken over 2,000 years ago, remain highly applicable today.

Though I’m sure I didn’t feel this way at the time, I was fortunate to read Plato as a college student. The Greek philosopher explored (among other things) rhetoric, or the art of persuasion. What Plato called a rhetorician would today be called a communications consultant or advertising agency creative director.

Plato’s teacher, Socrates, was put to death by the leader of Athens. He was accused of being a rhetorician. His accusers said Socrates made weak arguments seem strong, and strong arguments seem weak. Then and now, a skilled user of rhetoric could be a serious threat to the established order.

Athenian leaders didn’t target mathematicians or natural scientists, people who calculated spatial relationships or documented observable facts. Instead, they executed a wordsmith because he had the power to persuade.

That’s a little scary if you’re a wordsmith like me. While a character in Shakespeare advocated killing all the lawyers, it looks like Athenian authorities wanted to off all the ancient world’s speechwriters, messaging gurus, advertising folks and image-makers because they had the power to convince people that black was white, up was down, truth was falsehood and beauty was ugly.

Hmmmmm… sounds pretty pertinent today, what with “fake news” and “alternative facts”. One of my favorite authors, George Orwell, riffed on the enormous power of rhetoric in 1984, which by the way is enjoying newfound popularity these days.

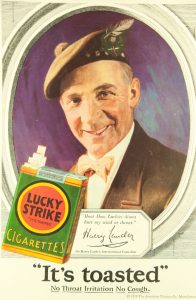

Coupling words and images, Madison Avenue’s forte, made smoking seem glamorous and sophisticated for decades. Eventually, the scientists caught up with image-makers, but not before millions got sick or died.

So perhaps the harsh judgment Athens imposed on Socrates was in some ways justified. Two thousand years before we had Madison Avenue and the advertising industry, the trial of Socrates revealed the awesome threat, and enormous power, of persuasion.

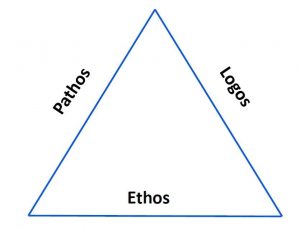

Logos, Ethos and Pathos

Let’s turn to Aristotle (left), another Greek philosopher who was a student of Plato’s and, later, a teacher of Alexander the Great. Aristotle said a public speech (basically the only form of mass communication in ancient Greece, two thousand years before the invention of the printing press) had three essential elements: logos (logic and facts), ethos (speaker’s credibility) and pathos (emotion).

A speech based on only one of those pillars would not be as strong as one that relied on two or all three.

Utilities are fact-based enterprises. Power plants and infrastructure are built using fact-based disciplines like engineering. Accounting and finance rely on math, an important fact-based discipline. Remember, “Enron math” wasn’t really math, it was a form of modern American fiction.

A person or a company is credible to the extent their statements can be verified as truthful. The next time someone challenges the law of gravity, take them to the 25th floor of your building and ask them to prove it by jumping.

Persuasion Relies on Sequencing

As an energy communications consultant, Aristotle would recommend using all three elements — facts (logos), credibility (ethos) and emotion (pathos) — to persuade customers, employees and other stakeholders. But he would also say the sequence with which you employed those three elements was as important as the elements themselves.

As an energy communications consultant, Aristotle would recommend using all three elements — facts (logos), credibility (ethos) and emotion (pathos) — to persuade customers, employees and other stakeholders. But he would also say the sequence with which you employed those three elements was as important as the elements themselves.

A farming metaphor may help here. Think of your credibility (ethos) as the seed, your emotional appeals (pathos) as the water and the facts (logos) as the fertilizer. Facts as fertilizer may sound a little sketchy, but stay with me here.

The sequence with which you apply seed, water and fertilizer to the land matters. Watering the ground without planting seed will produce no crops. Seeding and watering the ground is pointless if you don’t fertilize it. And if you apply fertilizer to a ground that has not been seeded with credibility and moistened with emotional appeals, you have wasted your time and money.

Communications Tip of the Month: In communications (as with everything else), substance is important but sequence is even more important. Start with credibility, then build an emotional connection to your audience before you bring the facts.

As fact-based enterprises, many utilities prefer to lead with the facts, believing facts will convince the audience. For example, a statement like, “We’re investing X amount of dollars to better serve Y number of customers” is meant to show a utility is running its business soundly.

Step One: Establish Your Credibility

But behavioral science has taught us that most decisions spring from emotion, not facts. Facts are what we round up to rationalize an emotional decision. “I needed some new shorts and I thought I looked great in these German lederhosen.”

As your energy communications consultant, Aristotle would instead recommend starting with credibility (ethos). The best way to speak authoritatively on something is to be an authority on it. The best way to establish, or maintain, or enhance, your credibility is to not lie. Ever. Don’t even shade the truth. Avoid euphemisms, especially if they are meant to mislead or deceive (which they often are). If you accidentally give out erroneous information, fix it fast and take responsibility.

Beyond not lying (which should be obvious), Aristotle would emphasize that credibility is built on deeds, not words. Say what you mean and mean what you say.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of credibility. We can see this high reliance on credibility everywhere we look. Conference speakers are introduced with a brief biographical statement showing their subject-matter expertise. News programs introduce guest interviewees with a mention of their position or accomplishments. When I read articles from authors with whom I am unfamiliar, I first check the biographical sketch that typically appears at the end of the article.

Once you establish your credibility, you can use that to your advantage when trying to convince someone of something you believe. But be careful. As Ben Franklin once said, “Glass, china and reputation are easily cracked, and never well mended.” I may be a pretty good writer, but I don’t know anything about nuclear physics or Venezuelan history. So I don’t hold myself out as someone who knows anything about those things.

Once you establish your credibility, you can use that to your advantage when trying to convince someone of something you believe. But be careful. As Ben Franklin once said, “Glass, china and reputation are easily cracked, and never well mended.” I may be a pretty good writer, but I don’t know anything about nuclear physics or Venezuelan history. So I don’t hold myself out as someone who knows anything about those things.

Step Two: Build an Emotional Connection

After you establish your own cred, or your organization’s, the next stop is pathos — appropriate appeals to emotion. Remember, people won’t care what you know until they know that you care. If you work for a utility that has established a track record of treating employees well, protecting the environment or investing in the community, don’t be afraid to stand on your record. But if you lack credibility on those topics, best to stay quiet and develop some credibility.

When I speak at conferences, I try to make a personal connection with the audience within the first 30 seconds. My theory is, if the audience doesn’t like me, they won’t accept my facts and recommendations. Because I want them to accept, or at least consider, my facts and recommendations, I want to find authentic ways to connect with them.

Step Three: Bring on the Facts!

When I counsel clients on public speaking, they are sometimes surprised to hear that an audience will listen to them, or not, based on whether they have made a personal connection to the audience. “But we know all this stuff and have all these facts,” they say. “Doesn’t matter,” I reply.

Once we have established our credibility and built an emotional connection to our audience, Aristotle would say then and only then can we layer in a few facts and recommendations. Why do facts come in third? A reader or an audience will only be ready to accept your facts if you have relevant subject-matter expertise bona fides and you have connected with them personally.

If you lack expertise or credibility, your stakeholders won’t believe what you say. And if you fail to connect with your audience, they won’t care about your facts.

Thomas Friedman (left) the veteran reporter and opinion-writer for The New York Times, said as much earlier this year when he told “Meet the Press” he was a big believer that “people don’t listen through their ears, they listen through their stomach. If you connect with them at a gut level, they’re not interested in the details. If you don’t connect with them at a gut level, you can’t show them enough details.”

In channeling Plato and Aristotle as energy communications consultants, remember:

- Words (and images) are powerful — so choose them carefully

- Effective communication follows this sequence:

- Establish your credibility (ethos)

- Make a personal connection (pathos)

- Marshall facts as needed (logos)

- Rinse, lather and repeat

Plato, Aristotle and Thomas Friedman would be so proud.